Are Moose Populations in the United States on the Decline?

In the United States moose populations are suffering as temperatures get warmer and heat stress and pathogens become more redundant among populations.

Gray and Brown Moose Standing on Brown Tree Branches by PickPik

The American Moose

The American Moose (Alces americanus) is the largest member of the deer family according to the Alaska Fish and Game Department. Moose have a few distinctive characteristics that separate them from other members of the family (1). They have huge flattened antlers that they use in defense from large predators that are common in their environments such as bears and wolves. Long legs and wide hooves are another profound characteristic of the moose that act as an additional form of defense from predators and allows them to walk in deep snowfall. Moose also have tubular hairs that trap air inside and provide insulation. Those hairs are why moose do better in colder climates versus warmer climates. Currently, moose inhabit 19 of the 50 United States as shown as in Figure 2 (2).

States Scaled by Moose Populations by Brian Brettschneider

Present Status Of Moose

Moose are considered keystone species and hold a high ecological importance. Their “job” is to eat aquatic and terrestrial plants to keep populations under control. Moose also act as food sources for other predators like bears and wolfs. Understanding how climate change impacts moose is not only important to their species but to other species and ecosystems as a whole.

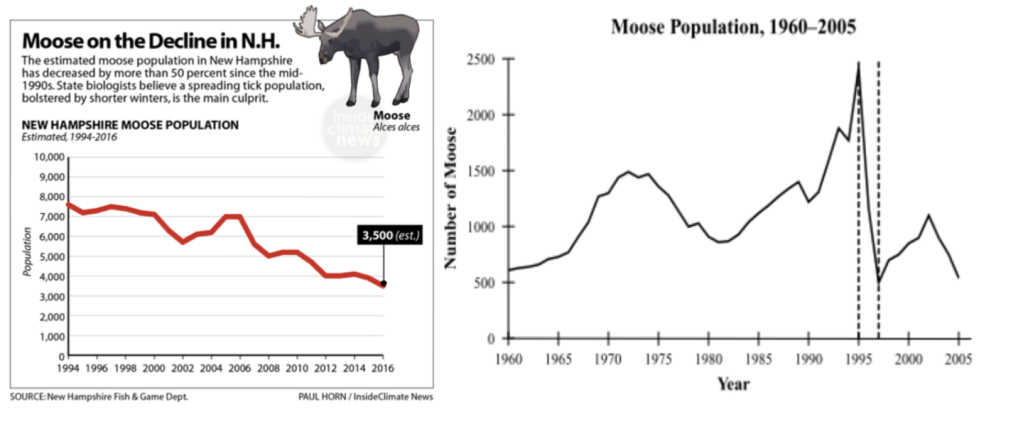

Recently there has been a decline in moose populations, as shown in Figure 3 and 4. In both graphs starting in 1995 there was a sharp decrease in populations, then a sudden rise of populations around 2005, then another sharp decrease. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) the year 2005 in the United States was recorded as an above average temperature year, so the overall climate was warmer. The sudden spike in 2005 is seemingly not temperature related and most likely random. But the sharp decrease after 2005 is most likely climate related as the next years recorded temperatures are also above average.

Figure 3: Decline of moose populations in New Hampshire from 1994-2016.

Moose on the Decline in N.H. by New Hampshire Fish & Game Department

Right:

Figure 4: Decline in moose populations in Michigan from 1960-2005.

Moose Population, 1960-2005 by Massachusetts Department of Education

Reasons For Decline

Induced Heat Stress

A study conducted in Minnesota sought out to explore the potential harm to moose populations with increasing temperatures due to climate change (3). Researchers saw that moose increase their oxygen consumption and respiration rates when temperatures reach above 57°F to reduce body heat through evaporative cooling (3). Evaporative cooling is a method for cooling down a hot mammal. When water evaporates from the surface of a mammal those surfaces become cooled and trigger dilated blood vessels to circulate cooled blood though the mammals body. In moose evaporative cooling is a physiological sign of heat stress (3). When a moose experiences heat stress their respiration and heart rates increase, they seek shade, cool winds and water, and they bed down and eventually stop foraging for food (6). Moose that don’t gain weight by the fall may not have enough body fat to survive in the winter months (6).

As mentioned previously moose have tubular hairs that trap air inside and provide insulation to keep them warm. Due to this built in insulation system that moose have they reside in colder climates because those hairs are built for them. When moose are in warmer climates those hairs are trapping in warmer air dramatically increasing their body temperatures on top of the additional body heat they have because the climate is warm. This puts them at additional risk for heat stress. When the climate is cold the air they trap is just enough to keep them warm.

Increase In Pathogen Load

Another cause of moose population declines are pathogens like brain worm and ticks that become more prevalent as temperatures get warmer (5). Ticks thrive in weather that is warm and snow free because it allows them time to search for a host when the cold won’t kill them. What are called “moose ticks” then take the opportunity to latch on to moose by the thousands. Multiple thousand ticks on one moose will drain its blood thus killing the it (4). A second pathogen, brain worm, happens when moose accidentally eat a gastropod, like a snail or slug. The larvae penetrate the moose’s stomach wall and travel to its nerves until it reaches the spinal cord and then the brain where the larvae grow and reproduce (5). The main target for brain worm are white-tailed deer. As white-tailed deer move north into moose territory due to warming temperatures they bring along brain worm which then switch to moose as hosts because they are bigger. Animals infected with these types of pathogens have more elevated body temperatures which make them more susceptible to heat stress (3).

What Can Be Done?

Conservation strategies to help moose populations are still being explored as the full effect of climate change on them needs to be studied further. Conservationist are suggesting starting with decreasing the rising temperatures associated with climate change. Cutting out hot temperatures could decrease heat stress and abundance in pathogens.

A good way you can contribute to decreasing global temperatures associated with climate change is by decreasing your carbon footprint or the amount of carbon dioxide you produce. Easy ways to reduce your carbon footprint include eating less meat, driving less, turning off and unplugging electronics when you are not using them, and to reduce the amount of waste you produce.

Sources:

(1) Bradford, A. (2014, November 14). Moose: Facts About the Largest Deer. Retrieved March 20, 2020, from https://www.livescience.com/27408-moose.html

(2) Maps, V. (2019, August 4). The U.S. states are scaled by moose population. Retrieved March 20, 2020, from

(3) Mccann, N., Moen, R., & Harris, T. (2013). Warm-season heat stress in moose (Alces alces). Canadian Journal of Zoology, 91(12), 893-898. doi: 10.1139/cjz-2013-0175

(4) Rines, K. (2014). New Hampshire Moose Study Roundup. New Hampshire Wildlife Journal, 2-4.

(5)New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. (n.d.). Brain Worm. Retrieved March 21, 2020, from https://www.dec.ny.gov/animals/72211.html

(6) Lowe, S. J., Patterson, B. R., & Schaefer, J. A. (2010). Lack of behavioral responses of moose (Alces alces) to high ambient temperatures near the southern periphery of their range. Can. J. Zool., 88, 1032–1041.

(7) National Temperature and Precipitation Maps. (n.d.). Retrieved April 23, 2020, from https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/temp-and-precip/us-maps/12/200501?products[]=nationaltavgrank&products[]=nationalpcpnrank&products[]=regionaltavgrank&products[]=regionalpcpnrank&products[]=statewidetavgrank&products[]=statewidepcpnrank&products[]=divisionaltavgrank&products[]=divisionalpcpnrank#us-maps-select